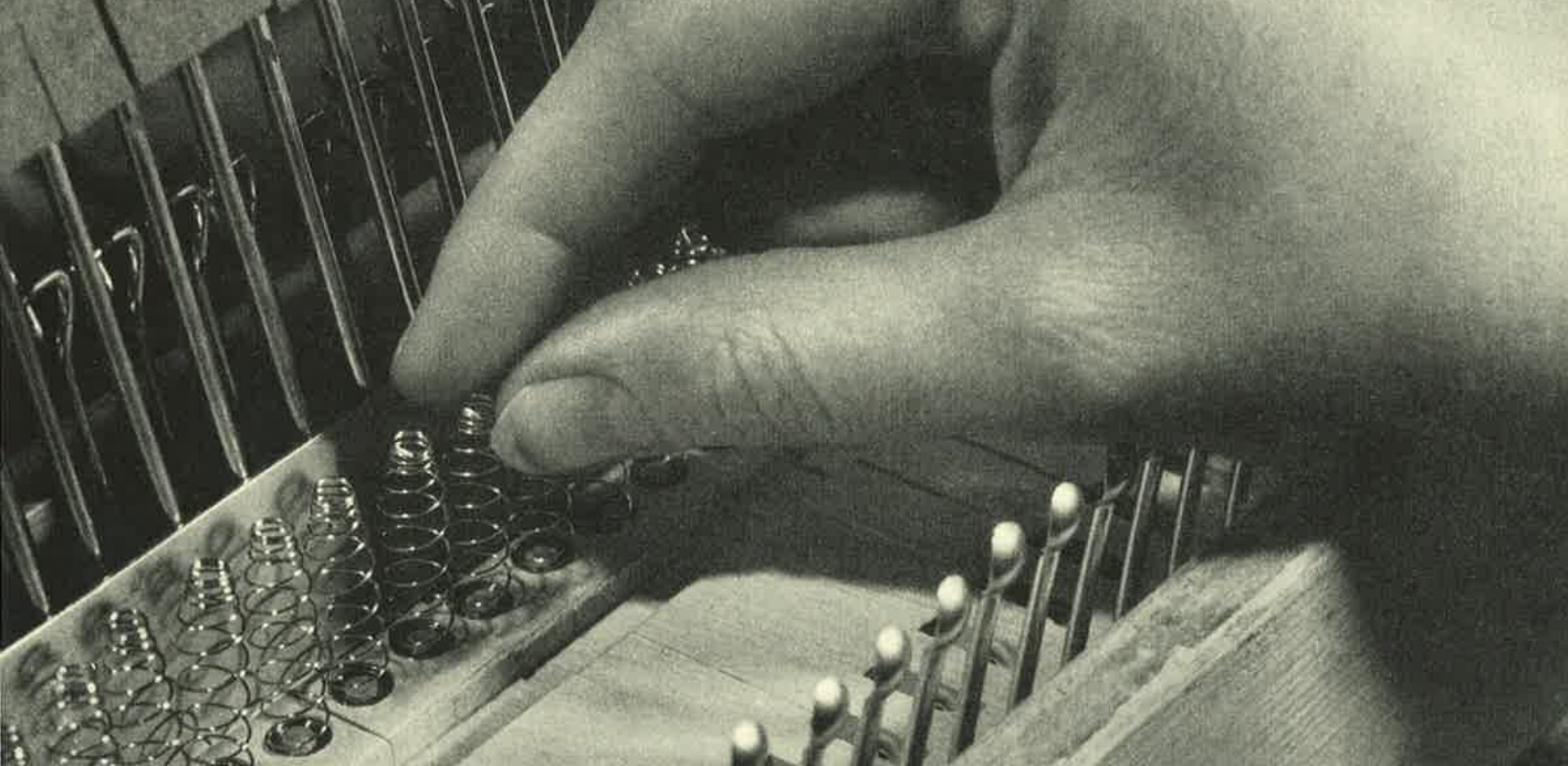

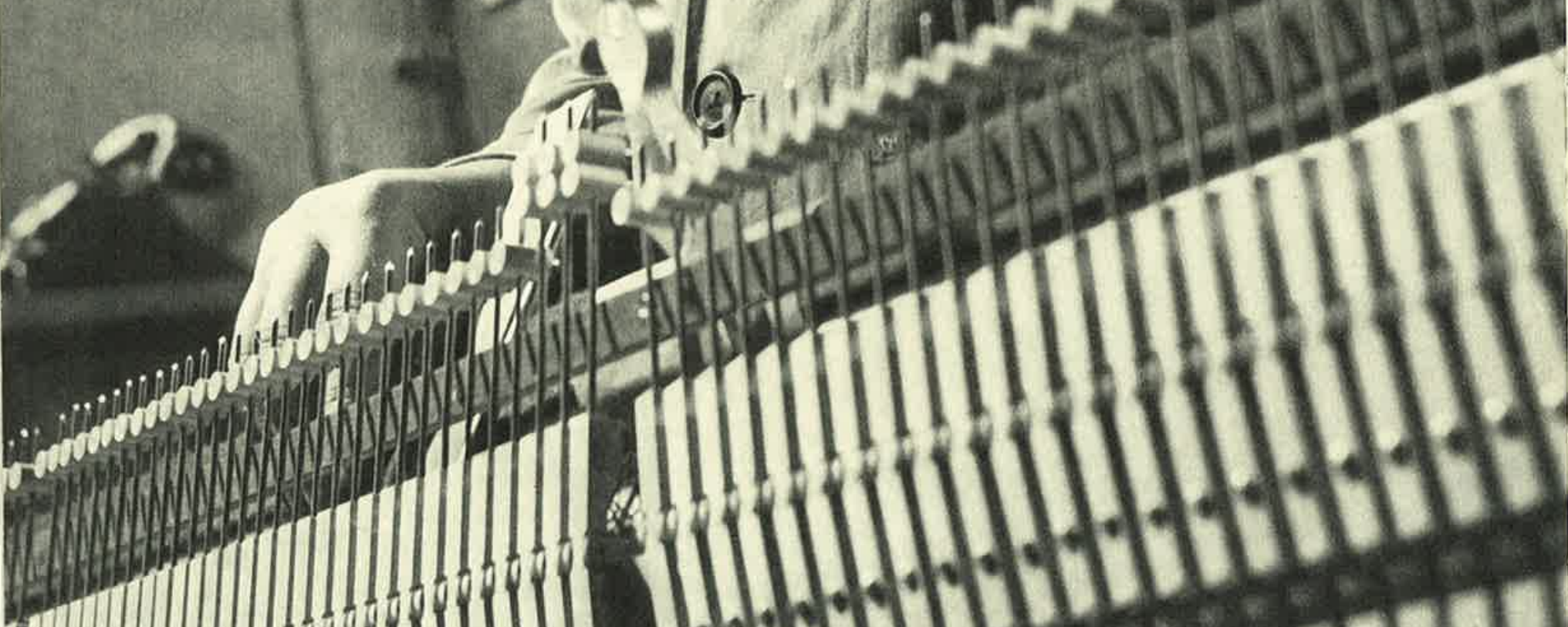

The history of the piano action

How this intricate keyboard mechanism developed

15th century

One of the world’s first customers for a piano was discovered in the Paris National Library Archives, in a treatise penned by Heinrich Arnold von Zwolle in 1440. Even that customer’s piano was probably very similar to the fortepiano. After that treatise, there are no documents mentioning fortepiano-like instruments until the end of the 17th century.

17th century

In the Renaissance and Baroque eras, through the end of the 17th century, people thought of keyboard-and-string instruments in terms of the sweetly melancholy clavichord or the metallic-sounding harpsichord family, which included smaller instruments like spinets. Of these, the harpsichord is the best-known – it is still played today. The color (spectrum) and richness of the sound were determined by the scale the instrument used, as well as by the mechanism used to make the strings vibrate.

18th century

The 18th century marked the ascent of the fortepiano, which – after centuries of further development – serves today as the ideal instrument for homes and concert stages alike. In 1705, a Saxon named Pantaleon Hebenstreit generated a great deal of attention with his hammered-dulcimer concerts. The hammered dulcimer is considered a forerunner of the fortepiano.

In 1709, Bartolomeo Cristofori of Padua built a fortepiano in Florence with a new hammer action; another design of his, dating to 1720, shows an action astonishingly sophisticated for his time.

Around the same time, the Frenchman Jean Marius submitted hammer action designs to the Paris Academy in 1716. Working independently, a German named Christoph Gottlieb Schröter presented two new designs to the Elector of Saxony and King of Poland in Dresden: one with upward-striking, the other with downward-striking hammers.

In 1731, Gottfried Silbermann constructed two fortepianos in Freiberg near Dresden with Prellmechanik or “bumping” actions, in which the hammers were articulated into individual flanges on the keys. Silbermann improved this action even further in accordance with Johann Sebastian Bach’s specifications. It remained in use for a long time to come as the “German action.”

As early as about 1730, instrument makers began setting their fortepianos upright; those instruments were the forerunners to our pianinos. The vertical strings required development of a new type of action. One well-known example is an upright fortepiano with joint mechanisms, designed in 1740 by the Italian Domenico del Mela di Gagliano.

In 1773, organ-builder Johann Andreas Stein of Augsburg, a student of Straßburg organ-builder Johannes Andreas Silbermann, improved Gottfried Silbermann’s Prellmechanik action by adding a spring-triggered escapement tongue for each hammer (instead of a fixed bumper rail). This action, which remained in use for more than a century without significant alterations, became known as the “Viennese action.”

In 1790, Philipp Jacob Warth of Untertürkheim, near Stuttgart, installed “English actions” into his square pianos. That action used a jack articulated to the back of the keys, which was pushed back by means of a screw.

19th century

The advent of the Classical era brought with it the rise of great pianists and piano composers. Hector Berlioz paved the way, followed by Chopin, Liszt, Clara Schumann, Wagner, d’Albert, and many others. They, more than anyone, are likely the reason that upright and grand piano technology progressed so rapidly – the artists’ desire to push the instrument further and further inspired instrument builders to make ever-greater advances.

By around the turn of the century (1800), production of upright fortepianos – known as pianinos – had begun in Vienna and the US. In Vienna, Matthias Müller began installing Viennese bumper actions with upright hammers into his pianos in the year 1800. In Dublin, William Southwell expanded upon these upright hammer actions in 1807 by adding another mechanism, the sticker action trigger mechanism.

In 1825, Sébastien Érard used a new grand piano action with a joint in the back of the key, which was connected to a second joint in the wippen via a setting pin; it translated force on the keys to the jack, which was rotatable and spring-loaded inside the wippen.

Sometime in the mid-19th century, a famous Parisian virtuoso and piano-maker named Henri Herz simplified Érard’s design into what was nearly its final form. Pianofortes with these actions were used in concert by the most celebrated pianists all over the world until the end of the century.

In 1845, Robert Wornum of London significantly improved the upright action design. His version axle-mounted a jack to a wippen screwed onto the back of the key, which allowed precise, uniform regulation of the escapement using an adjusting screw. Additional resonance-improving features added around 1850 resulted in piano actions essentially of the type we still use today.